Developed by Cornell researchers, the program deduced the natural laws without a shred of knowledge about physics or geometry.

The research is being heralded as a potential breakthrough for science in the Petabyte Age, where computers try to find regularities in massive datasets that are too big and complex for the human mind and its standard computational tools.

"One of the biggest problems in science today is moving forward and finding the underlying principles in areas where there is lots and lots of data, but there's a theoretical gap. We don't know how things work," said Hod Lipson, the Cornell University computational researcher who co-wrote the program. "I think this is going to be an important tool."

Condensing rules from raw data has long been considered the province of human intuition, not machine intelligence. It could foreshadow an age in which scientists and programs work as equals to decipher datasets too complex for human analysis.

Lipson's program, co-designed with Cornell computational biologist Michael Schmidt and described in a paper published Thursday in Science, may represent a breakthrough in the old, unfulfilled quest to use artificial intelligence to discover mathematical theorems and scientific laws:

Half a century ago, IBM's Herbert Gelernter authored a program that purportedly rediscovered Euclid's geometry theorems, but critics said it relied too much on programmer-supplied rules.

In the 1970s, Douglas Lenat's Automated Mathematician automatically generated mathematical theorems, but they proved largely useless.

Stanford University's Dendral project, was started in 1965 and used for two decades to extrapolate possible structures for organic molecules from chemical measurements gathered by NASA spacecraft. But it was ultimately unable to assess the likelihood of the various answers that it generated.

The $100,000 Leibniz Prize, established in the 1980s, was promised to the first program to discover a theorem that "profoundly affects" math. It was never claimed.

But now artificial intelligence experts say Lipson and Schmidt may have fulfilled the field's elusive promise.

Unlike the Automated Mathematician and its heirs, their program is primed only with a set of simple, basic mathematical functions and the data it's asked to analyze. Unlike Dendral and its counterparts, it can winnow possible explanations into a likely few. And it comes at an opportune moment — scientists have vastly more data than theories to describe it.

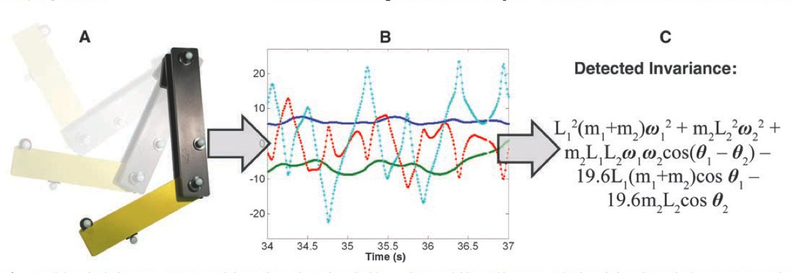

Lipson and Schmidt designed their program to identify linked factors within a dataset fed to the program, then generate equations to describe their relationship. The dataset described the movements of simple mechanical systems like spring-loaded oscillators, single pendulums and double pendulums — mechanisms used by professors to illustrate physical laws.

The program started with near-random combinations of basic mathematical processes — addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and a few algebraic operators.

Computer Program Self-Discovers Laws of Physics

Computer Program Self-Discovers Laws of Physics

Image.